THE BARRIERS TO CREDIBILITY

BY ROBERT K. WRIGHT

There is a long-enduring process to becoming an effective educator. It is a process that is both academically grueling and monetarily unfulfilling. There is a special dedication you must have when serving the youth, especially those who come from disadvantaged communities. For one teacher, in particular, the quest for excellence has taken him to graduate school at Columbia University’s Teachers College, in hopes of being able to bring the best learning experience to poor minority youth, an often neglected and vulnerable population.

While pursuing his undergraduate degree in Behavioral Science, he realized that sometimes real change can only occur when those who lived within particularly adverse conditions return to do just that, change them. He is both the epitome and obstacle of credibility. He has overcome many of the same obstacles as the youth who come from marginalized communities much like the one he himself had survived while growing up in NYC’s public housing. Do you believe this man to be qualified to teach in a classroom? Would you say he is capable of understanding the sociological factors that contribute to an adolescent’s learning experience inside the classroom, and the trauma they may be experiencing outside of it? Here’s a better question: Do you want this man to teach your child?

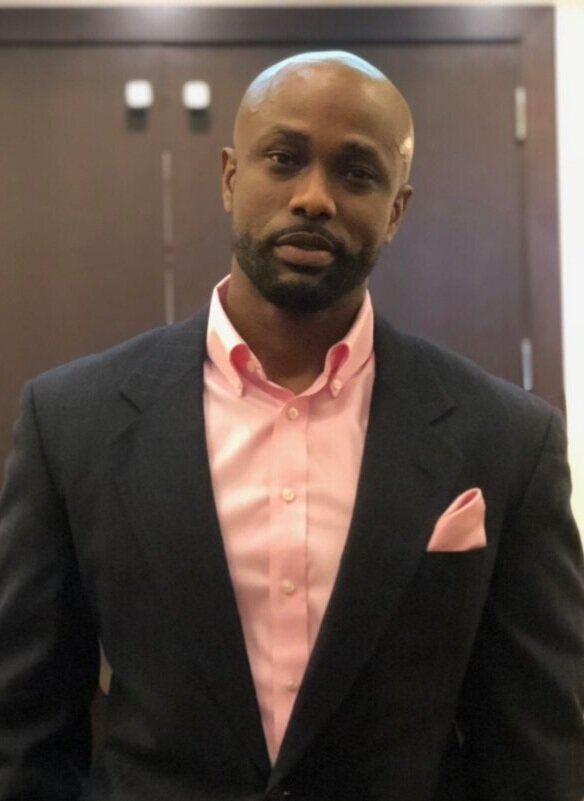

Just one thing. When he was 18 years old, he was convicted and sent to prison for assaulting a man. Does that dissolve any of the admiration you may have developed for this person I’ve been raving about? Of course, it does. It changes everything. You may be able to rationalize it later using compassion and even empathy if your life has somehow been affected by incarceration. But, be honest, you flinched a little, didn’t you? That man is me. Let me reintroduce myself. My name is Robert K. Wright. I'm a Black, Ivy-League-educated, entrepreneur, published author, educator, and a violent felon. Every opportunity that comes my way is shadowed by a mistake that I made over 20 years ago. I cannot receive my teaching certification because the Department of Education has denied me access to a public school in order to complete my observation requirements. Even a Master’s degree in English education is not appraised to be enough, in the case of a felon, to receive admittance into a classroom. Do I no longer have any value to society? Has anyone even considered the positive impact that I could have on students who have been cast away to preparatory prisons disguised as alternative schools, where they are surrounded by law enforcement and metal detectors? A place where most of the students have criminal records and most of the teachers are too afraid to educate them. These kids continue to self-destruct until they are aged out, no longer the D.O.E’s. responsibility. Eventually, these kids are considered adults who are ushered into incarceration, where they continue to fuel the public school-to-prison pipeline.

It does not matter that I was only a few months too old from being considered a child at the time, and there were no minors involved in my conviction. Or that I have experience working with youth in after-school and college prep settings. None of this matters because I’m a felon. The most degrading part of it all is that I’m forced to relive this trauma, over and over again, every time some gatekeeper to my professional aspiration demands that I explain. Their abrupt reproachfulness reminds me that I must plea in my most humblest, “please give me a second chance, sir” tone. Because any sign of frustration would only validate that I am in fact a threat to society. Not hiring me can always be morally rationalized because the “what if'' will always be assumed too severe to be worth the risk. It’s hard to overcome such justifiable discrimination. It’s not easy trying to counter the natural impulse society has to always choose fear over faith in humanity. But I can tell you what it does to the millions of our citizens returning home from incarceration: It drains us.

My ambitions are always met with felonious restraint, and my accomplishments always have an awkward acceptance. Why must I keep confessing my sins to you? Where were you when my neighborhood was drug-infested? You stood by and watched as the police used Stop and Frisk to patrol my NYCHA complex, beating and arresting us for loitering in the same buildings we lived in. Where were you when I saw my friends killed right before my eyes? No pat on the back, and certainly no counseling like you gave others. And I owe you an apology? An apology for surviving? I survived the most violent decades in urban American history. Between 1980-96 New York State averaged over 2,000 murders a year, peaking in 1990 at over 2,600 murders. Along with the introduction of crack, and the nefarious claws of addiction that it brought, the inner city was a melting pot of savagery and morally exempt perseverance. Are you still going to pretend to be surprised that violence had such an impact on my life? The more important question is, why did I have to live in fear and feel the need to carry a gun to navigate my own community? It seems you only left me with two options, be a victim, or be violent.

I have no regret for surviving, I owe you no explanation for refusing to submit to the fatal statistics that brands my complexion. I eluded death to fall victim to a slow and agonizing societal fatality. All I did was survive, and my reward was incarceration. That was your response, mass-incarceration. You did not help us living in these impoverished violent communities. You could have written a check investing in our neighborhood’s prosperity. Instead, you gave us a bill. A crime bill that further devastated our neighborhood. I’m in no way asking for your sympathy or remorse. Just give me a damn chance. When is my punishment over? You threw me in a cage as a boy, and somehow I managed to return to a good man. What else must I do to have you treat me as the man I am, not the mistake that I made? Because apparently there’s no college degree or life experience you deem worthy of admittance back into your all too perfect world.

“I am not free. I have simply shed the veil of incarceration for the coat of a felon. Both fall extremely short of emancipation.”

If you leave people like myself no room for redemption you will corner us into desperation. Desperation for me means that I’ll probably change my major, and choose a career that is not predicated on your forgiveness. Attribute that to my great support system of family and friends, and a college degree. But for so many others, this desperation will look like destruction. You will take this opportunity to then point your fingers and justify your reluctance to give out second chances when in reality you have only set us up to fail. You didn’t give us the resources, housing, and compassion that we needed to successfully assimilate back into society.

The hell with it if you won’t let me into your institutions and departments. I’ll just find an entrance that will. And if that door closes in my face, I’ll just build a structure of my own and George-Jefferson-walk on through. To those souls still living behind the walls, anticipating your next parole date, dreaming every night of the day you are free, I say your freedom will feel more constricting than your incarceration at times. The mounting responsibilities and endless rejection that you will be confronted with will feel just as restrictive as those cold steel bars that lock you in at night. You will have to find that same resolve that kept you sane while in the S.H.U. And maintain that same determination you have to keep your humanity intact when correctional officers deny you your basic human needs. I am not free. I have simply shed the veil of incarceration for the coat of a felon. Both fall extremely short of emancipation.

We are fighting so hard to get people out of prison. But what will be waiting for them? Returning people to society after decades of imprisonment without housing and employment opportunities is even more inhumane than the prisons we seek to have them removed from. In prison, I was fed, and had a bed to sleep on. When I’m released back into society where I now must pay for my meals, and find housing, I am constantly denied the opportunity to do so, because of my felony record. How come captivity provided me with basic human essentials to exist, but liberty affords me no avenue to meet the abundance of responsibility that I’m handed the moment I am freed?

All I want to do was give our kids a reflection of themselves that they can be proud of. I was one of these kids. I needed to see someone who looked like me. Someone who overcame all the trials I thought that I was facing alone. Someone to tell me that everything will be alright. I apologize, on behalf of a pigheaded society, to a youth who would have benefited immensely from having a teacher who made mistakes. Mistakes that would have been turned into lesson plans. The academic achievement gap exists because they won’t let those who understand you be the people who teach you. Maybe I’m not worthy of a second chance. I had my opportunity to get it right the first time. I can carry that burden. But how do we continue to look at our children and not even give them the best first chance they can have?

Robert K. Wright is a research assistant at the Center for Justice at Columbia University and a graduate student in pursuit of his Master’s degree in English education. Robert has participated in a number of panel discussions and events addressing social injustice. He has worked on and researched a number of articles examining the effects of trauma and punitive practices on urban communities. Much of Robert’s interest in social justice comes from him being directly impacted by our criminal justice system and being from a community affected by mass incarceration.